Chinatown—and Our Town

The classic film speaks brilliantly to our time too

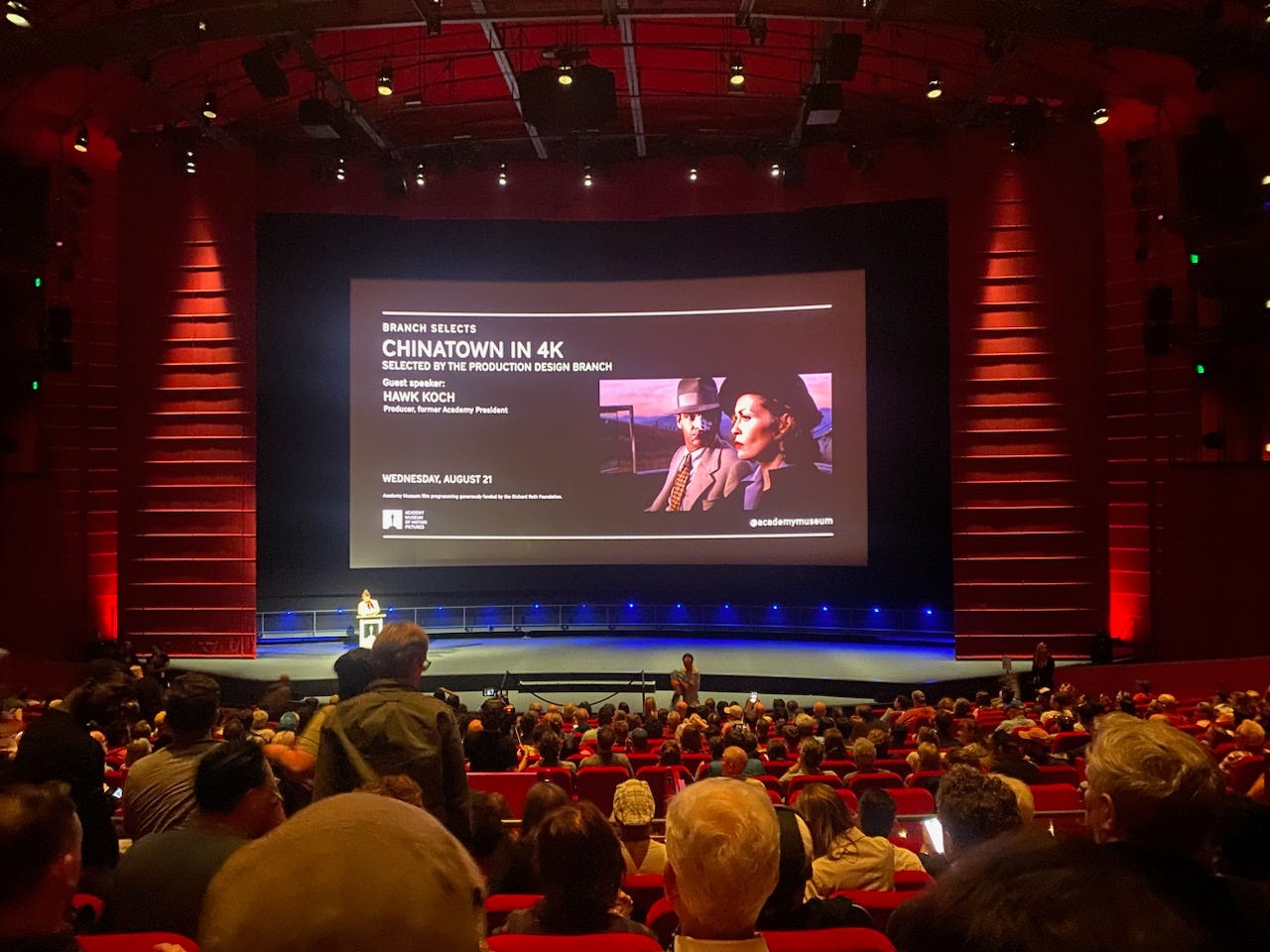

I took in a screening last night of Roman Polanski and Robert Towne’s dark masterpiece Chinatown at the grand 952-seat theater at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures. It was a full house, and the melancholy began even before the 4K print unspooled (if that word is still apt).

The evening began with a curator’s introduction that included a thank you to once-mighty Paramount for providing the digital cinema print, a sad reminder of that beleaguered studio’s glory days. Next came remarks from producer Hawk Koch, a former president of the Academy who served as first assistant director on the 1974 film. His anecdotes—featuring location scouting across the LA Basin and a smashed black-and-white television set (you had to be there)—spoke of a world in which studio filmmaking was still seat-of-the-pants and no matter how bleak the story the Sun still shone on a City of Dreams.

Then the neo-noir epic rolled (that word another relic of sprockets and film reels), and as a vintage Paramount logo jittered on screen in a digital simulacrum of celluloid, I couldn’t help but reframe the signature line from Sunset Boulevard, itself a Paramount production: the pictures didn’t get bigger, the studios got smaller.

And, indeed, the traditional studios—which until recently we called “the majors”—once seemed as massive and formidable as dinosaurs astride the land. Now, trapped in a La Brea tar pit arguably of their own making, they simply seem like dinosaurs of another sort, debt-ridden corporations desperately shedding shows and staff as they write off multi-billion-dollar losses.

Spoilers ahead …

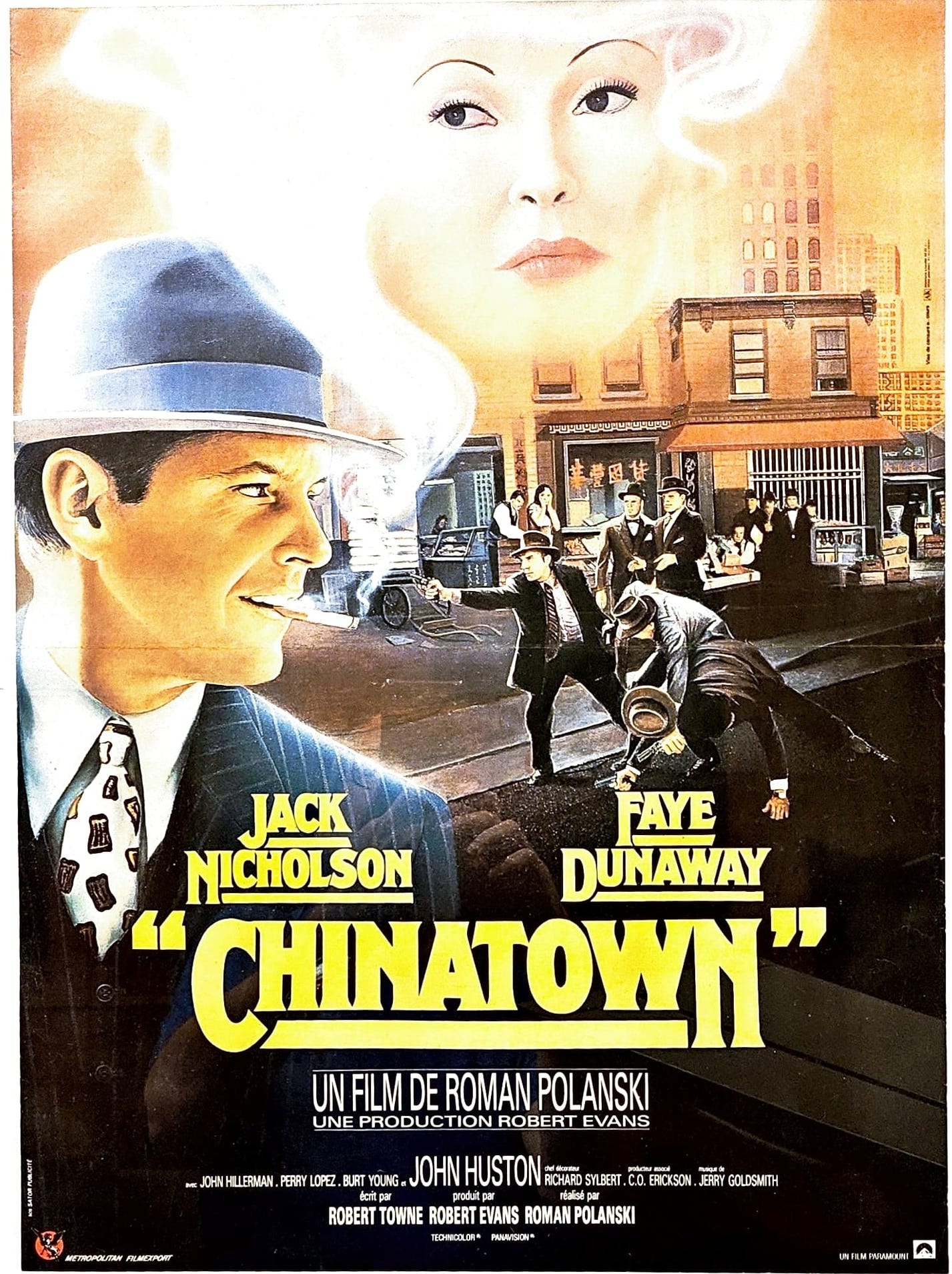

As the Paramount logo faded out and the sad strumming of a harp gave way to the melancholy wail of a brass horn on Jerry Goldsmith’s haunting soundtrack, the narrative began to unfold, a tale of wealth, incest and patriarchal oppression set against the backdrop of a true story from the 1910s transposed and fictionalized into the ’30s and refracted through the lens of the early ’70s, an era in which innocence and innocents reeled from the onslaught of government duplicity surrounding the Vietnam War and the Watergate burglary and cover-ups.

The film’s backdrop is brilliantly elemental: it’s the story of massive water diversion—some say theft—that built the Los Angeles metropolis and corruptly enriched the powerful. Los Angeles is a city on the edge of both waterless desert and undrinkable ocean. And while freshwater brings life, saltwater too plays a key part in the plot—and, it should be noted, is also the key ingredient in human tears, which are plentiful in this story of murder and depravity.

I can’t be sure but I may first have seen the film a half-century ago at the home of Paramount’s then-president, Frank Yablans, whose son Robert was a high school friend of mine. Whether we watched Chinatown or one of the Godfather films or maybe the first Star Trek film—or perhaps all of these iconic movies, oh, the glory that was Paramount!—I do recall at least one visit, and perhaps several, to the Yablans suburban New York manse where a uniformed waiter served chicken from a platter before we decamped to a home screening room staffed by a studio projectionist. Home theater, indeed, with the clackety-clack of a 35 mm projector as soundtrack.

But it was just a few years later that I encountered one of the earliest signs that Hollywood’s future would be digital. It was 1981 and I took a summer job in Cambridge at a company called Symbolics that just a few years later became the first dot-com ever registered. (I later worked at another Cambridge firm, BBN Labs, which a decade earlier had invented email and the Internet/ARPAnet itself—twenty years before Al Gore got wind of the Internet, in case you were wondering.)

On the East Coast, where I worked, Symbolics’ early AI workstations were coveted by three-letter agencies and shadowy consultants from McLean, Virginia. But on the West Coast, I learned, the company had a sales office in what to me seemed an almost mythical place, called Calabasas, and I was told that our systems were used to create the special effects on the first, 1982, Tron movie.

I would be lying if I said that I connected the dots and drew the natural inferences from Moore’s Law and its corollaries that speak to the exponentially rapid increases in power, speed, memory and storage capacity, coupled with decreases in size and cost, that characterize computers. Few people did.

Hollywood has been yoked to technology from the inceptions of film and television but for decades it was all analog—celluloid, vacuum tubes and their arcana, all slow to change. But in the early 1990s—coincidentally, the same time I arrived in Los Angeles for a front-row seat—digital effects and digital editing began to become commonplace, and the game began to change as well, because now Hollywood found itself wedded to a partner that evolved at increasingly breakneck speed.

And then distribution went digital, first in theaters and then in homes. We’re still in the midst of the streaming revolution, even as we begin to face the opportunities and challenges that generative AI is likely to be to bring.

But if the meta story of Chinatown made me nostalgic for a world I’d never actually experienced—1970s Los Angeles? 1930s? 1910s?—the story itself couldn’t be more timely.

“What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” Jack Nicholson’s private detective J.J. Gittes asks the villain of the piece, local plutocrat Noah Cross, played with seething menace by John Huston, himself a director of classic noir.

Cross’s simple answer cuts as viciously as the stiletto that earlier disfigured the PI’s nose: “The future, Mr. Gittes, the future,” he hisses. In Chinatown, destiny is always for sale. Notably, Cross consistently and deliberately mispronounces his adversary’s name—as “Gitts” rather than “Gitt-is”—a belittling tactic which may remind you of a certain politician.

Indeed, Cross’s reply rings contemporary bells on both the local and national stage. Here in Los Angeles, Hollywood faces a future purchased by tech billionaires and their multi-trillion-dollar enterprises. Working- and middle-class writers, cast and crew struggle to survive in a contracting industry.

And nationally, as a neofascist centimillionaire stalks the presidency, and corruption and hate no longer bother to cloak themselves in even gossamer fabric, the country is poised to decide—probably by narrow swing-state margins—whether the future is beholden to dark forces and highest bidders or whether sunny California optimism can break through the storm clouds.

So, a screening of Chinatown indeed couldn’t be more timely, and little surprise that the theater was packed. Is this classic film a story of the 1910s, 1930s or 1970s? It doesn’t matter, because the tale is timeless—and the saltwater tears Chinatown sheds are for all of us.

Brilliant analysis of the film's poignancy and the changing chaotic times we live in. We pray for sunny optimism.

Well done! I’m jealous, I love CHINATOWN!